[p. 77] The English Royal Chancery: Structure and Productions

The two centuries between 1199, the accession of King John, and 1399, the death of King Richard II, may well be regarded as the golden centuries of the English royal chancery. The major advances can be traced back to the Angevin system of government introduced by Henry II and to the development of the accounting office, the Exchequer, and its head the king’s vice-regent, the Justiciar. But a fully developed chancery with a system of registration is not discernible before 1199. Towards the end of our period, however, the three offices of Chancery, Privy Seal and Signet were issuing annually between them some 30,000 to 40,000 letters — perhaps more1 — and of these a fair proportion were enrolled on the great rolls of Chancery.

The first list of the officials of the royal household and their allowances of c. 1136 provides for a chancellor and a master of the scriptorium. The latter, Robert de Sigillo, probably effected the sealing of documents. His duties had so grown that by the end of Henry I’s reign he was receiving a commensurate rise to accord with his new status.2 The next entry concerns the chaplain in charge of the king’s [p. 78] chapel and the relics and it is clear that the chancellor is responsible for the chapel services and the whole clerical establishment. Forty years later in c. 1176, according to the discussion between master and student known as the Dialogue of the Exchequer, the Chancellor has a clerk to look after the King’s seal in the Exchequer, and the master of the writing office provides scribes to write the «roll of the Chancery» (a copy of the Great Roll of the Pipe, the Exchequer’s main account roll) and the writs and summonses of the Exchequer.3

It is much to be regretted that we do not have a similar discussion between master and student as to how the royal chancery operated. If we had, perhaps it would outline the homely nature of the household office, lending out its clerks who were still to be found carrying out chapel duties and who were attached to particular chancellors. Most of the early chancellors (between 1066 and 1189) were deans or archdeacons, resigning when a bishopric came their way. Chancery’s organization was almost certainly inferior to Exchequer’s.

The transformation of Chancery began with the justiciar-chancellors of the 1190s, William Longchamps and Hubert Walter. Longchamps was never actually called justiciar, but he acted as the king’s chief representative and chief of the council of regency from 1189-91, holding the king’s seal, and he was chancellor from 1189 to 1197. Hubert Walter was justiciar from 1193 to 1198 and chancellor from 1199 to 1205. He had been brought up in the household of his uncle, Ranulf de Glanville, justiciar from 1179 to 1189. After the king, the justiciar was the most important man in the country, the king’s viceroy when he was abroad. Vast sums of money had to be raised for the wars, for the crusade, for Richard I’s ransom. Organization and records were needed and this explains the beginning of the great series of administrative measures and parchment rolls that breathe the name of Hubert Walter. Furthermore the growth of the common law began to increase the demand for judicial writs and to stretch the resources of government and hence of chancery.

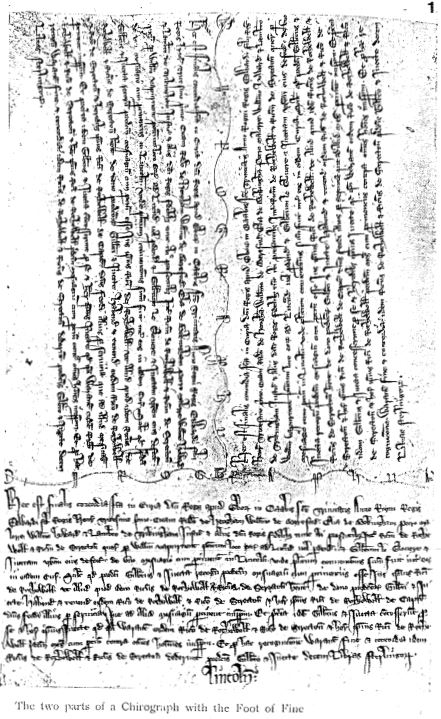

[p. 79] The introduction of the feet of Fines, the Jewish arche, the plea rolls, the Carte Antique, and the Chancery rolls and the development of letters patent and letters close are all to be associated with these years. The feet of fines commencing in 1195 at the command of Hubert Walter provided a method of registration with the royal court, the foot remaining in the royal archive. (See plate 1, an example of 1303). The Jewish arche set up in 1194 by Hubert Walter provided record centres and the official writing of transactions in which Jews were concerned in towns. (See plate 2A, chirograph and plate 2B, a writ of King Henry III, under the seal of the exchequer of the Jews, for the deposit of the foot.) The plea rolls commence in 1194 and possibly the coroners’ rolls. The first enrolment on the Carte Antique rolls was made between the spring of 1190 and the spring of 1198. It is likely that they originate under Richard I. They are enrolments of charters for religious houses, probably made by clerks from those institutions. The Pipe roll for 6 Richard I (1194-5) records that the men of Beverley owe 15 marks for the enrolment of their royal charters in the Exchequer and Round surmised that the crown had a roll on which charters were recorded by the middle years of Henry II.4 It seems that charters were kept in the Treasury under Henry I though not yet enrolled.

Registration in England definitely originates in the Exchequer. The series of Pipe rolls begin in 1130 under Henry I. They were closely followed by the memoranda rolls and there was a fine roll or oblata roll (recording sums of money and gifts offered to the king) in existence by the last year of Richard I’s reign. Chancery registration does not commence until 1199 with the Charter rolls from King John’s first year (see pl. 3, section of the charter roll for 1290). By the second year there are nascent close rolls (see pl. 4, section of the close roll for 1389) and by the third year patent rolls (see pl. 5, section of the patent roll, Nov.-Dec. 1202). Further divisions were made under Henry III when the liberate rolls begin (1227) for the writs of liberate.5 The Gascon rolls were also instituted under Henry III. Under Edward I, Scots, Welsh and Roman rolls were introduced. The rotuli Alemannie begin under Edward II and the French rolls under Edward III.

[p. 80] The regulation on Chancery fees which was issued at the instance of Chancellor Hubert Walter on 7 June 1199, twelve days after King John’s coronation and his own appointment, is the only comment we have on the structure and organization of Chancery at this important time. Mentioned are the chancellor, vice-chancellor, a sigillifer and a protonotary. By appointing Hubert Walter as his chancellor John secured continuity in the administration. The ordinance announced a return to the scale of fees for Chancery documents as under Henry II. Clearly there was a danger that royal government would break down if there were no confirmations and no new charters. Richard I had grossly overcharged. Henceforth the old payments were to be reinstituted for letters patent of protection and for simple confirmations. The regulation is closely connected with the commencement of the Charter Rolls in the same year, the first of King John, and although letters patent are registered in the Charter Rolls for the first two years it is clear that there is a growing distinction between letters and charters and between letters sent open and letters sent close.6

The next description of Chancery occurs in a legal treatise, the so-called Fleta, written by a lawyer towards the end of Edward I’s reign (1307). It represents chancery as being largely concerned with the issue of original or judicial writs. It is on the way to developing legal powers and has furthermore virtually been separated from the household. From the treatise we learn that there are two groups of clerks — the senior and superior clerks and the inferior or junior clerks. The seniors ordered writs (the preceptores), wrote the original ones (the prenotaries) and examined the work of the lower clerks. The juniors write the stock writs, the writs «de cursu». Their writs are to carry their names and are to be examined by the senior bench before despatch. They «hold office by favour of the chancellor» and to prevent them «from demanding excessive payments for their writing, it is laid down that the clerks both of the justices and of the chancellor shall be content [p. 81] with one penny and no more for every writ they write».7 The prime concern of the author is chancery’s growing activity as a court not its range of activities as a writing office of all varieties of documents issued under the great seal.

By the time of our last, and only real, Chancery ordinance (1389), a completely structured office is in existence, separate from the household. Here are present under the chancellor twelve clerks of the first bench. They were already that number by 1327 and from about 1370 they are described as Chancery masters. Each of the Chancery masters had three clerks under him, but the senior, the keeper of the Chancery rolls, had, following this ordinance, six clerks of his own. Two of the remaining eleven were preceptores, authorizing writs, six were examiners and one, from 1336, a notary who wrote and enrolled international documents.8 The twelve clerks of the second bench, who wrote the charters, letters patent and the writs, consisted of two clerks of the crown, who wrote the writs of the crown, with two assistants each, the clerks of the petty bag who wrote the writs «diem clausit extremum», the clerk in charge of searches through the Chancery rolls in the Tower of London and the clerk who read the records and pleas of Chancery. Each of these had one assistant. Twenty-four cursitors wrote the stock writs and the «ad quod damnum» writs. All work had to be examined by the examiners of the senior bench. No one is to reveal the secrets of the Chancery. They are to live in a common dwelling, and they are not to take bribes.9

The royal seal, in the custody of the chancellor, had always been the king’s great double-sided seal of which a duplicate had been made for Exchequer use by the 1170s, but by Henry III’s reign, if not earlier, it had acquired a distinctive design. (See plate 6A for the obverse of [p. 82] the great seal of King Henry III, and 6B for a fragment of the great seal of Edward III used on a writ close). The justiciar had his own seal and on occasion he sealed exchequer writs which were attested by one exchequer official.10 By the reign of Henry III a separate Exchequer seal of different design existed. King’s bench and common pleas also acquired separate seals and special deputed seal matrices were made for Ireland, Scotland and Gascony (see pls. 6C, Exchequer seal of Edward I, 6D, Chancery seal for Ireland of Richard II, and 6E, seal of Edward II for Scottish affairs). The «control of the seals» and the development of new, small, private and secret seals mirrors the changes in the power structure (pls. 7 & 8, privy seals, and secret seals and signets). It also determines the form and style of Chancery documents. It is not certain that Henry II had a personal seal. For Richard I there is some evidence, for John there is proof of his possession of a private seal though no example of it survives.

The reigns of Richard I, John and Henry III are the crucial ones in the early development of the private royal seals and allowed, in the case of the last two monarchs, the conduct of much business through the household offices. Under John the Chamber became important: under Henry III and his successors it was the Wardrobe that assumed prominence. The development of letters and the letter form is linked with the growing formula of «teste me ipso» and in the case of letters close directly with the private seals. The change-over from charters to letters patent is illustrated by this hybrid document of John (see pl. 9) which has some of the features of the charter (cf. pl. 10, a charter of Richard I) and some of letters patent. A charter of Henry III, dated per manum, and of letters patent, teste me ipso, under what came to be the accepted forms can be seen in plates 11 and 12. The normal method of warranting under the great seal becomes by writ of privy seal as illustrated by plate 13 — a privy seal warrant for the issue of letters patent under the great seal appointing Richard Lyonn constable of Dover castle from the first year of Edward III.11 The decline in the number of charters and the growth in the number of letters close and letters [p. 83] patent is manifested by the introduction of separate rolls for close and patent letters in the second and third year of John. Letters patent had been entered on the charter roll in John’s second year.

Throughout the thirteenth century the separation of the chancery from the household became more pronounced, though the reign of Henry III is full of paradoxes. The minority of the young king brought greater powers for the Marshal and the bishop of Winchester who attest during these years and the appointment of a chancellor by the council in 1218 was to lead by 1244 to the demand of the magnates in parliament to have a permanent say in his selection. In 1232 the office of justiciar was abolished and the «chancellor of the exchequer» took over the functions of the former clerk of the chancellor so that the Exchequer came to have an independent chancery with a chancellor and clerks of its own. By the end of Edward I’s reign a large number of exchequer writs were issued under the supervision of the clerk of the writs and they and the letters patent were enrolled on the memoranda rolls by the remembrancers. The earliest reference is found also in 1232 to a clerk of chancery, no doubt to distinguish him from clerks of other departments, but there is still a blurring of chancery and chapel. With the appointment of a chancellor in 1260, who did not farm the office but received a fixed salary, the office naturally declined in importance and desirability and the office of the hanaper was introduced for the collection of chancery fees. Before the accession of Edward I the chancery was to be found more and more at Westminster and less and less dependent on the movements of the king. The demands of a war administration also changed the significance of the chancery. At the beginning of 1293 the chancellor’s fee was restored and the «hospicium» of the chancery was split off from the household.

The Privy Seal

The organization surrounding the privy seal was centred on the household and the wardrobe. From 1232 Peter des Rivaux, keeper of Henry III’s Wardrobe, had custody of the privy seal. On one occasion in 1238, writs directed against the chancellor, Ralph Neville, whose appointment to the bishopric of Winchester the king was resisting, were written and dated in the Wardrobe at Woodstock. They found their way on to the chancery rolls only after the separate sheet on which they [p. 84] were copied was surrendered. It was then stitched in to the main chancery roll.12

The king might use the privy seal for a variety of personal and administrative purposes. All the surviving documents sealed with Henry III’s privy seal are warrants for issue under the great seal and no Wardrobe rolls survive to indicate the range of correspondence which was certainly wide. There is evidence for rolls of privy seal documents regularly compiled by Wardrobe clerks from 1290-7 and including letters which for reasons of confidentiality could not be copied on the Chancery Rolls.13 Edward I and Edward II used the privy seal for all purposes, sending instructions to Chancery and Exchequer, but mainly our sources for study are the letters resulting from the warrants — the letters and writs, both patent and close, the bills (administrative orders) and the indentures for military service.

The Wardrobe’s position was such that under Edward I the Wardrobe official who kept the privy seal was described as the «private chancellor of the king».14 Its close attendance on the king, perambulant as the old Chancery had been, caused it to be both flexible and powerful. It accompanied the king on military campaigns and met the demands of war. The account books show that the bulk of the expenditure was channelled through it and troops were paid by the Wardrobe. It could issue debentures, promises of future payment and in the first half of Edward’s reign loans from Italians came directly to the Wardrobe.

By 1312 the barons had secured control over the privy seal. Ordinances of 1311 had declared that the clerk appointed to keep the privy seal should, like the chancellor, be appointed by the king in parliament [p. 85] and on the advice and with the approval of the barons. Henceforth the privy seal office became a second writing office and a clearing-house, sending out formal warrants to Chancery, Exchequer and other offices, letters and writs, both patent and close, bills ordering payments and diplomatic letters to foreign rulers. A privy seal writ close was issued by Edward III to the abbot and convent of Westminster ordering them to release the stone of Scone to the sheriff of London. Dated at Bordesley on 1 July 1328, it was sealed according to the method in use before 1345, the document being folded twice vertically and the tie then passed round it and crossed. The seal was then applied where the tie crossed. Traces of the red wax may be seen on the dorse of the document and the address on the tongue in French is clearly visible (pl. 14).15 Letters patent under the great seal which had been warranted by privy seal writ were used for appointments and licences (pls. 15 and 16). But letters patent under the privy seal were also issued directly. On 22 February 1370 Edward III, in letters patent under the privy seal on a tongue, appointed his clerk, William de Mulsho, to act as his attorney to receive seisin of certain lands (pl. 17). On 3 May 1378, Richard II by privy seal bill, the seal applied on the face, ordered his receivers for war to pay wages to John Haukyn and others (pl. 18). A warrant to Chancery for a writ to summon Thomas Mydlington of Southampton to appear before the council (1392) was signed with the name of John Prophet, privy seal clerk and the first clerk of the Council (pl. 19).16 By 1400 there were ten or twelve privy-seal clerks, seniors and juniors.

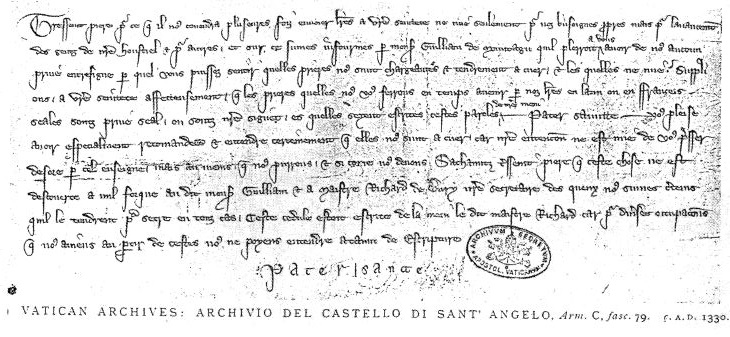

Once the privy seal had become separated from the king and within a year of the appointment of Roger of Northburgh as keeper of the privy seal, Edward II had a new secret seal. The hostility of parliament and council was from now on directed at the secret seals which made their appearance at this time. The king’s secret seals could be used for various business. In 1335 the king issued an order under the secret seal («sous notre secre seal a Londres») for letters to be issued under the privy seal for Bartholomew Tyrel to be given the church of Old [p. 86] Radnor (pl. 20). Edward III petitioned the pope to attend to letters «in Latin or French under the privy seal or under our signet» (see plate 21). The signet became the main private seal from Richard II’s reign. The signet’s keeper was the king’s secretary, who nominally had four clerks. It, too, became the object of the council’s discontent being used (as the secret seal had been) to express the royal prerogative and to bypass the Privy seal office in warranting great seal documents. In 1377 at Kennington, «in the absence of our privy seal», Richard II used the signet to authorize the issue of a protection for six months for Geoffrey de St Quintin («Seyntquyntyn») en route for Calais on royal business (pl. 22). In 1388 Parliament forced Richard II to promise to stop issuing signet letters to the damage of the realm, and one of the chief charges against Richard was his abuse of the signet. In the absence of his own signet in November 1389, Richard II sent a letter close under the queen’s signet, but he also signed it with his sign manual «Le roy R S sans departyr» (see pl. 23).17 The importance of the sign manual which appears with Richard II increased at the expense of the signet as that too became the secretary’s seal and hence less under direct royal control. From Richard II’s reign petitions granted received the sign manual and were called signed bills.

This brief sketch can scarcely do justice to the great range of documents issuing from the English chancery nor to the subtle and detailed work done by Dr Chaplais, Professor A.L. Brown and others and to past scholars of administrative history, amongst whom the names of Tout, Galbraith, Wilkinson, Richardson and the anonymous editors of the great series of rolls stand out. I have tried to draw attention to the peculiarities and individual characteristics of some of the types of document prevalent in England in these two centuries rather than concentrating on the types which undoubtedly by the end of the period were in the mould of the major chanceries of Europe. An advanced royal government meant that the English Chancery produced more royal documents at an earlier date than its neighbours. The innovation of registration brought clearer classification of documents issued in the king’s name.

List of Plates

| 1 | Feet of fine (1303) |

| 2.A | A Chirograph recording the conveyance of a house in Norwich by William de Melleford, hostiarius of the Wardrobe, to Isaac of Norwich son of Abraham the Jew and his heirs. |

| 2.B | Writ of King Henry III to the chirographers, both Christians and Jews, of Norwich, under seal of the exchequer of the Jews, for the deposit of the foot of the above to be placed in the arche at Norwich. (Westminster Abbey Muniments 6715 A and B).> |

| 3. | Section of the Charter Roll for 1290. |

| 4. | Section of the Close Roll for 1389. (J. and J. pl. 31). |

| 5. | Section of the Patent Roll for 1202. (J. and J. pl. 10a). |

| 6.A | Obverse of great seal of Henry III. |

| 6.B | Fragment of the great seal of Edward III used on a writ close. (Chaplais pl. 25). |

| 6.C | Obverse and reverse of Exchequer seal of Edward I. (Archaeologia 85, pl. 84). |

| 6.D | Obverse and reverse of Chancery seal for Ireland of Richard II. (ibid. pl. 91). |

| 6.E | Seal of Edward II for Scottish affairs. (Antiquaries’ Journal xi pl. 28). |

| 7. | Privy seals of Edward I (no. 1), Edward of Carnarvon (2), Edward II (3,4), Edward III (5,6). (Tout v pl. I: for full reference see footnote 14). |

| 8. | Secret seals of Edward II (nos. 1,2) and signets of Richard II (nos. 3-6). (ibid. pl. IV). |

| 9. | Royal charter of confirmation of King John illustrating transition from royal charter to letters patent. |

| 10. | Charter of King Richard I. |

| 11. | Charter of King Henry III. (Fuller Collection, University of London Library, I/19/2). |

| 12. | Letters patent of King Henry III (1271). (ibid. I/24/1). |

| 13. | Privy seal warrant for issue of letters patent under the great seal, 1 Edward III. |

| 14. | Privy seal writ close (Westminster Abbey Muniments 51112). |

| 15. | Letters patent of Edward III (1349). (Fuller I/21/6). |

| 16. | Letters patent of Richard II (1394). (Fuller I/21/10). |

| 17. | Letters patent of Edward III under the privy seal on a tongue. (Chaplais pl. 27a). |

| 18. | Privy seal bill of Richard II (1378). (ibid. pl. 27b). |

| 19. | Warrant to Chancery for writ of summons under the great seal (1392). (J. and J. pl. 30b). |

| 20. | Order under the secret seal of Edward III for privy seal letters. (J. and J. pl. 22c). |

| 21. | Petition to the pope of Edward III, written by his secretary, Richard de Bury, at the bottom of which the king himself has written «Pater sancte». (J. and J. pl. 22b). |

| 22. | Signet order (bill) of Richard II. (Chaplais pl. 27c). |

| 23. | Sign manual of Richard II on a letter close issued under the queen’s signet in absence of his own. (Chaplais pl. 18). |

[p. 88] Nos. 2A, 2B and 14 are reproduced by the kind permission of the Dean and Chapter of Westminster; nos. 11, 12, 15 and 16 by the kind permission of the Librarian of the University of London Library.

J. and J. = C. Johnson and H. Jenkinson, English Court Hand A.D. 1066-1500 illustrated chiefly from the Public Records (Oxford 1915) 2 parts Pt II plates.

Chaplais = P. Chaplais, English Royal Documents King John — Henry VI 1199-1461 (Oxford 1975).