[p. 681] The Chancery of the Duchy of Brittany from Peter Mauclerc to Duchess Anne, 1213–1514 (Tafel XXII–XXIX)1

The Breton chancery fulfilled the same function as chanceries in other late medieval states by serving primarily as the writing office for letters issued in the name of the ruler. Such letters were normally authorised by the duke and his councillors – either by that small semi-permanent group of advisers who handled the day-to-day affairs of the duchy or by larger bodies called together for a particular purpose like Parlement or the États (which assembled fairly frequently from the late fourteenth century) or by informally summoned groups called to advise on special issues2. By the fifteenth century the letters issued could cover every matter of business from great matters of state down to the most insignificant administrative detail; the duke exercised in this respect [p. 682] full sovereign powers over his subjects within the duchy. He corresponded and entered into treaties with foreign princes as an equal. At the head of his administration – both of the small ducal council and of the chancery itself – was the chancellor. It was under his authority that clerks and secretaries wrote the letters and the appropriate seals were attached. The two administrative organs of council and chancery, for long directly linked in the position of the chancellor, were in the end officially joined in the last ordonnance (1498) concerning the chancery in its late medieval phase and served between them as the chief guardians of the duke’s rights3.

Misunderstandings could arise. When in 1404 secretaries were reminded not to ‘escrire lettres qui puissent grever ou porter dommage au royaume ne duchie de Bretaigne, ne autres lettres de grand pois pour envoier hors desdiz royaume et duchie sans deliberation de conseil’ or when in 1459 it was decided ‘touchant les lettres que le duc en a escript a Paris, il convient que le duc escripve a son procureur et gens de son conseill a Paris que la cause soit porseue o diligence, non obstant quelxconques lettres que le duc par inoportunes requestes inadvertment ou sans deliberacion de son conseil’ had issued, we can see this friction. The chancery, just like the council, might act on its own authority. Individual clerks might be persuaded to issue letters unknown to council; the chancellor himself, as some charges in 1463 allege, might collude with them for private gain4. But in normal circumstances council and chancery cooperated to protect ducal interests and this role was not purely defensive. It involved the active preparation of what would now be called propaganda to promote those interests. Their reciprocal functions, even common personnel (for at any one moment other councillors besides the chancellor also worked in the chancery) can be emphasised at the outset. The chancery gave public expression to decisions taken in council.

What is known about the chancery’s records, organisation and personnel in Brittany during this period? First, its position, like that of the council, becomes progressively clearer as the period unfolds. When Jacques Levron catalogued the letters of Peter Mauclerc, ruler of the duchy between 1213–37, including documents in which Peter’s name occurred, not simply limiting himself to those apparently issued by the chancery during his reign, he listed 283 entries. But of these he cited only 19 as still surviving originals relating to [p. 683] Peter’s rule, whilst the name of the chancellor who seems to have served for most of his reign appears just once in this catalogue5. Léon Maître compiled a similar catalogue for Charles de Blois and his wife, Jeanne de Penthièvre, who ruled for a comparable period (1341–64) just over a century later, listing just 59 documents6. It is true that this was a time of civil war and there may be some truth in the claim that their successor, John IV (1345–99), deliberately attempted to destroy the documentary evidence of his predecessors’ rule7. It is also unfortunately true that Maître’s catalogue is woefully inadequate as a survey of the surviving ducal letters of this period8. Yet the contrast with the next reign is startling. In my recent edition of the letters of John IV for the period 1357–99, I have listed over 1200 entries. Whereas for Blois the names of 23 secretaries or clerks have been brought to light, the identity of his chancellors still remains obscure. But in the case of John IV, over 50 chancery clerks are known by name and a reasonably reliable sequence of chancellors can be constructed9. A keeper of the ducal archives (trésor des chartes) was appointed and in 1395 he compiled the first, still surviving, inventory of the ducal records10.

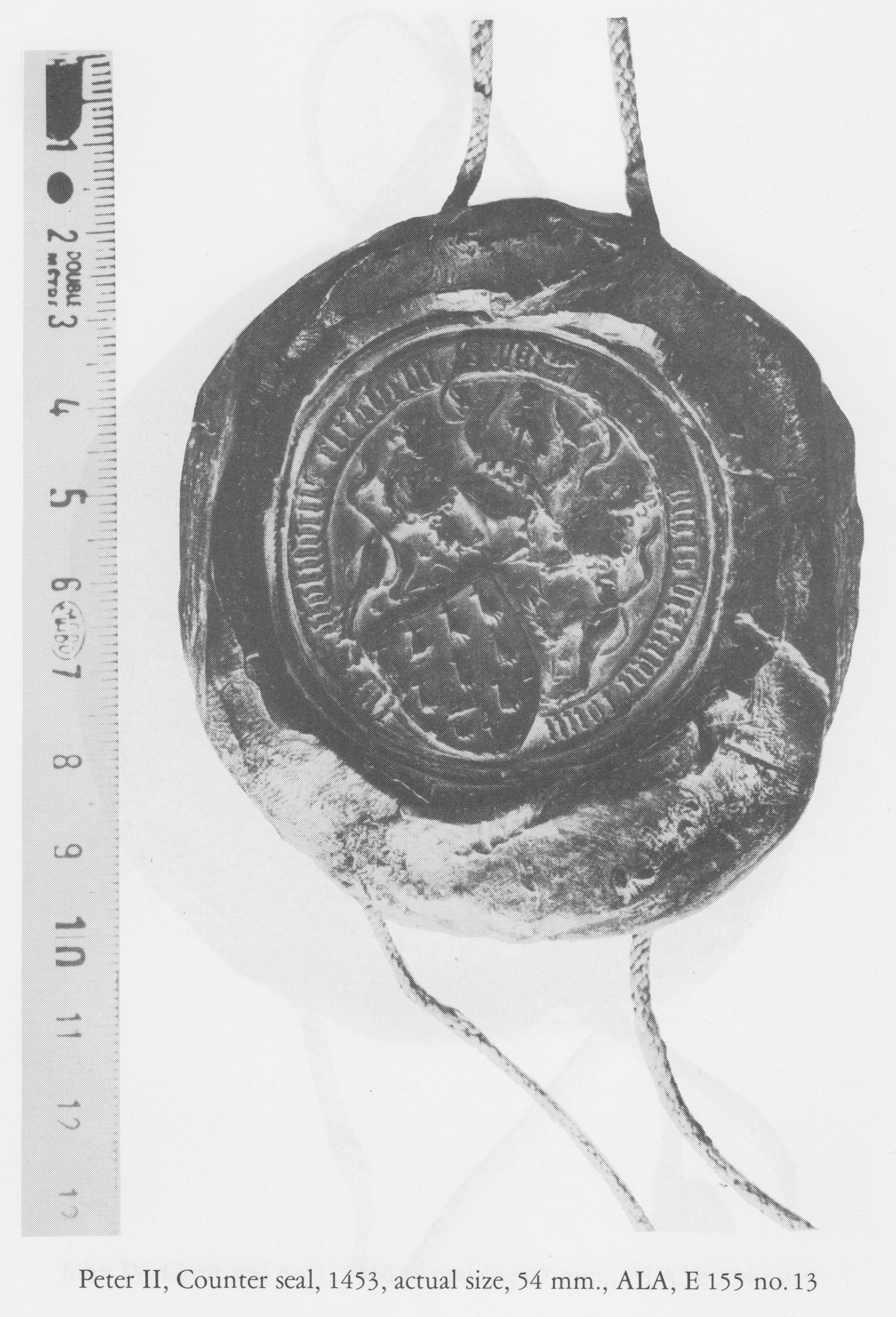

This advance in available evidence continues with the next reign. There is an ordonnance issued jointly in 1404 by Philip the Bold, duke of Burgundy, and his ward John V (1399–1442), which throws some light on the organisation of the chancery and payments to its staff11. For a brief moment between [p. 684] 1404–8, fragments from two series of overlapping registers have been conserved in their original form or later transcripts12. These provide for the first time summaries of considerable numbers of letters issued from the chancery, with the result that for a reign of comparable length to that of his father, John V’s collected letters number some 2700 in the remarkable edition of René Blanchard, even though the editor unfortunately omitted the letters issued during the minority (1399–1405). The names of over 160 chancery clerks are known for this period13. The records of the next three short-lived dukes (Francis I, 1442–50; Peter II, 1450–7; Arthur III, 1457–8) have been less well preserved14. But from 1462 there survives a broken series of original registers covering some 20 of the last 52 years of the period in detail, while eighteenth-century transcripts or publications provide some indications of the contents of now lost registers for a further four years15.

From them can be obtained a comprehensive view of ducal government at work as it expressed itself through the formal work of the chancery or, in the case of the register for 1490–1, of an administration in crisis during the last days of the independent duchy. From February 1491, in particular, this register shows increasing disorder in the enrollment of documents. There are many blanks for letters which were to be written up subsequently but never were. Folios have been misplaced or lost and office routine as a whole appears to have collapsed almost entirely between March and July. Only the siege of Nantes in 1487 had provoked similar irregularities on an earlier occasion on such a scale16. Subsequently, when Brittany came into the hands of Charles VIII of France, he officially suppressed the post of chancellor and replaced it with a governor of the chancery. Letters were issued largely in the King’s name, omitting mention of his wife, the former duchess Anne, and no registers [p. 685] have survived17. At present the series recommences with the register for 1503 – Queen Anne, acting in her own right as duchess, had re-established the chancery two days after the death of her husband in April 149818 – and only two registers are missing for the last ten years of her reign. In comparison with entries in the registers of Francis II or in those of the first years of her own reign, their content is now much more formal, though it is unfair to say that they only contain remissions in full as one recent commentator has stated19. Clearly, however, with the disappearance of the independent Breton state after 1491, most of the political and diplomatic material which predominated when Brittany was still at war with France also disappears. From Anne’s reign, too, there are a number of documents throwing light on the functioning of the chancery like a unique fragment of a daily register of fees, collected on behalf of the chancellor, for the issue of letters between October 1489 and 1 February 1490 and other material relating to the payment of secretaries, especially between 1498 and 151220. There are the two important ordonnances – that relating to the abolition of the chancery by Charles VIII in 1493 and that to its re-establishment in 1498 – which add considerably to a precise knowledge of its personnel. In addition important efforts were made to provide suitable accommodation for the preservation of the records at Nantes both by Charles VIII and Anne. In the early sixteenth century the archives were placed in wooden boxes (cassettes) in cupboards (armoires) and given a reference number which served to identify them until the compilation of the Inventaire sommaire in the nineteenth century. The original boxes still survive, whilst the contemporary reference numbers on documents which have been scattered since the early sixteenth century have enabled archivists to identify several formerly kept at Nantes21. As a result the reign of Anne is by far the best documented in the period under study, though as the records relating to the inquiry into the alleged misconduct of Chancellor Guillaume Chauvin in 1463 show, a penetrating light can occasionally be thrown onto chancery practices at earlier periods.

[p. 686] Despite this increasing wealth of evidence and considerable interest in all aspects of the history of the duchy during the later middle ages, studies of diplomatic and the systematic edition of ducal letters have not advanced as quickly as might have been expected given the fundamental work on the Breton chancery done with admirable thoroughness by Blanchard almost a century ago in his monumental edition of the letters of John V. He included a survey of the earlier history of the chancery and its archives. He paid particular attention to the origins of registration which, in some form, he traced back to the thirteenth century22. He also provided a full description of the diplomatic of documents for John V’s reign, which with some modification also seems to hold good for earlier periods too23. It would be futile to attempt to emulate that description here, but it should also be noted that in addition Blanchard kept detailed notes on ducal acta from other reigns and that these notes, together with those of his literary executor, Abbé Bordeaut, himself a very competent historian, still form a remarkable source of information on Breton diplomatic. Both fichiers are now deposited at the Archives départementales de la Loire-Atlantique24. A few additional letters of John V have been discovered since Blanchard’s day but general studies of the Breton chancery have advanced little25. The ill-fated Marcel Planiol, a near contemporary of Blanchard, provided some useful pages on the chancery in his Histoire des institutions de la Bretagne, but unfortunately neither Levron nor Maître in their later catalogues attempted a serious study of the diplomatic of their respective dukes’ chanceries26. Although a welcome start has been made to calendaring the late fifteenth-century registers in diplomas undertaken by students at the University of Nantes (a series which is currently being revived under M. Jean Kerhervé at the University of Western Brittany at Brest), by [p. 687] their nature these studies of a single annual register preclude a serious comparative approach to the diplomatic of the period27. The main addition to the corpus of available material has been the recently completed edition of the letters of John IV, in which parallels and contrasts with his son’s reign have been commented upon briefly. More particular attention has been devoted to the seals of that duke which have been shown to display a hitherto unsuspected richness of variety, form and symbolism which is in line with the increasingly independent aspirations of the duke as a ruler28. Although this variety cannot be matched in the seals of any other rulers of the duchy, comparative studies of sigillography in Brittany will in future be considerably assisted by the compilation at the departmental archives at Nantes of a photographic record, now available for consultation, of all the surviving seals in that repository.

To sum up the results of a hundred years’ labours, the letters of two dukes have been edited or calendared in their entirety, those of two others have been listed (one very inadequately), but ten out of the fourteen rulers of the duchy between 1213–1514 still await definitive editions of their letters which would enable a sound comparative study of diplomatic and of the development of the chancery to be written. The lack of serious studies of the letters of John I (1237–86), Francis II (1458–88) and Anne (1488–1514) – who briefly issued letters jointly with her first husband, Maximilian, king of the Romans – are especially regrettable29.

We may now turn to the organisation and role of the chancery. The period from 1213 to the mid-fourteenth century is a dark age about which little is, [p. 688] or perhaps can be, certainly known, for the separate existence of a chancery cannot be definitely established. The succession of a Capetian cadet in 1213 seems to have coincided with a number of changes in diplomatic practice. It was, perhaps, natural that Levron, who first directed attention to these (which he viewed favourably), should have attributed them largely to the influence of a French cleric who accompanied Mauclerc to Brittany and became his chancellor, Rainaud, future bishop of Quimper. ‘Aux usages anglais, he wrote, qui étaient jusque-là observés dans la rédaction des actes, il substitua des règles françaises. Sous sa direction, les scribes de la cour ducale adoptèrent des habitudes d’ordre, de clarté. Rainaud imposa même ces pratiques aux chancelleries secondaires (monastères et petites cours féodales)30.’ These views have been repeated by subsequent writers, although they now seem to be largely misconceived31. It is true that in comparison with charters dating from the period of Plantagenet domination in the duchy (c. 1156–1206), there are some grounds for arguing that a majority of Mauclerc’s letters are somewhat simpler in form, technically more ordered and their latinity clearer32. But it is at a cost.

Those interested in administration or in diplomatic will regret the absence of witness lists, a paucity of details on the circumstances of issue, often imprecise dating clauses, a dearth of indications on the type and mode of attachment of the seal, failure by the scribes responsible for the documents to append their names and an absence of other useful additional notes in comparison with both earlier Breton documents and those issued later. It is, in fact, the loss of just such features which makes study of the Breton proto-chancery and its organisation during the thirteenth century such a barren one at present – rather like that of the royal chancery at a slightly earlier period33. Evidence for personnel from the chancellor downwards is almost entirely lacking34. [p. 689] In the absence of any paleographical studies, the identity of different ducal clerks and their hands is unknown, and not until some aid is afforded by financial accounts late in the century may we guess some names. For it was not until the reign of Charles de Blois (1341–64) that it became normal practice for clerks to sign their names again, whilst lists of witnesses only begin to re-appear consistently from c. 1330. Warranty notes such as ‘Par le conseil’ or more detailed references to the circumstances of issue or on the seal used only appear at all regularly from the end of the thirteenth century35. At that period, and indeed for the rest of the Middle Ages, advantage was particularly taken of formal meetings like Parlement, sessions of the Chambre des Comptes and also of the États to publicise grants and privileges36.

It may be gathered from all of this that in the thirteenth century Breton chancery practices, in keeping with other aspects of the rudimentary administration of the duchy, lagged considerably behind the much more sophisticated chanceries of France or England37. To take the example of the missing clerk’s signature; already in Edward I’s reign in England the legal manual Fleta had stated as axiomatic that every royal writ ‘had to bear the name of the scribe who wrote it, so as to engage the scribe’s responsibility towards the purchaser of the writ38.’ In French royal letters, likewise, the addition of the name of the clerk became a feature of late thirteenth century documents and [p. 690] from this period separate lists of royal notaries begin to survive39. This similarly was to become a rule in the Breton chancery – the letters enrolled on the surviving registers all bear the name of the clerk responsible for them – but the practice does not begin to operate until c. 1342, perhaps as an innovation by Blois’s French clerks40.

It is thus not just on the grounds that Levron’s views are simplistic, nor his evident prejudice against the supposed ‘English practices’ of the Plantagenets, nor his touching faith in the ability of Rainaud to impose standard practices not only on the Breton chancery but on other scriptoria in the duchy, that I would now judge his opinions inadequate. Rather, it is clear that the changes he observed, whilst owing something to the installation of a new régime – and one manifestly much influenced by Capetian example – were also part of a general movement in Western Europe. This was fuelled by growing literacy and familiarity with written records, their increasing number and the need to streamline and standardize office procedure. ‘La grande nouveauté du règne (de Philippe Auguste), it has recently been argued, est précisement le recours constant à l’écrit41.’ It was a time of experiment in documentary forms in response to pressures which demanded more business-like, precise and unambiguous official records though, conversely, in the course of development, there was a period when some records temporarily became less precise, too simplified, lacking authenticating detail. Something of the same process may be seen at work in the royal chancery as standardization occurred42.

In other words, although some of the changes which happened in the thirteenth-century Breton proto-chancery may be attributable to the deliberate decision of the chancellor and his staff to adopt certain specific practices in imitation of other influential chanceries – notably the French, but one might suspect the English and papal chanceries as well – or because of increasing familiarity with Roman law and notarial practice, many usages seem to have crept in gradually, even surreptitiously, over long periods. It was surely by a similar process of imitation, rather than at the behest of the chancellor, that [p. 691] letters written elsewhere in the duchy adopted similar forms. The result was that certain formulae were favoured (or ignored) for a period before being replaced (or omitted) by slightly different forms. Thus the relaxation of precise detail on dating, notable in Mauclerc’s letters, is gradually replaced in John I’s reign by more informative clauses; conversely John I’s early letters make only the most sparing references to the seal which was attached, frequently, indeed, omitting all mention of it43. Yet the overall appearance of ducal letters, like royal ones from the 1190s, remained fairly constant from one reign to the next44.

As far as we can tell, at this stage the duke made regular use of only two seals – the great seal (with a counter seal) and a secret seal45. In the fourteenth century, dukes from Charles de Blois began to use privy seals and signets much more freely and, from early in John V’s reign, a seal of majesty, a unique usurpation of sovereign rights by a French prince46. As in other chanceries there developed a close connection between the particular seal used, its mode of attachment, the colour of the wax and the type of letter to which it was appended. In the thirteenth century the dukes used white or yellow wax for solemn grants (later considered a royal prerogative), and by the late fourteenth century it was normal to use green wax for grants in perpetuity (appended to the most solemn and elaborate letters on multi-coloured silk laces) and red wax for other business. Any deviation from the usual routine was noted on the document as an added precaution – the use of a departmental or institutional seal, a seal of absence, a particular signet or privy seal. A final authenticating feature was the autograph of the duke. John IV seems to have been the first duke to have annotated his letters extensively (from 1372), not [p. 692] merely with his signature. His successors were usually less free with their holograph comments, but all continued to sign throughout their rule. In contrast to the royal practice by which certain clerks imitated the royal sign manual, Francis II in 1483 took advantage of the introduction of printing to have his normal signature engraved on a block for application to routine financial documents to lessen the burdens of government47.

The most obvious external change to occur in the form of thirteenth-century Breton documents was the way in which French was adopted as a new language for charters from the late 1240 s. This innovation may be considered not as a deliberate act of state, an early anticipation of the ordonnance of Villers-Coterêts, but one brought about largely by a natural geographical diffusion of that language in written sources. At first used only for documents relating to the affairs of the ducal family and great nobles, it reflected the spoken language of the Breton court and, presumably, the desire of the parties involved to be as fully informed as possible on their legal position. Then documents in French rapidly began to appear across the whole duchy between c. 1250–80, even in the remotest western districts, until they were even used for transactions between religious houses involving no lay parties48. The language’s advance in Brittany came a generation or more after French had begun to be employed regularly for similar transactions in north-eastern France, about twenty years after its incursion into Saintonge, Poitou and the Charentais, but only a few years after its appearance in documents issued in the Middle Loire region – Anjou, Touraine and Berry49. Royal and princely chanceries had been remarkably conservative, even resistant to the use of the vulgar tongue in France, but it is interesting to note that the first royal letters issued in French by Louis IX in 1254 involved John I of Brittany as one of the parties50.

[p. 693] A superficial survey of protocol in letters issued by Mauclerc and his successors (in the notification, address, salutation or ducal title and the dating clauses) reveals that there were certain, limited, standard forms which continued in use from reign to reign, subject only to necessary modifications dependent on personal circumstances – the addition or omission of an extra territorial title, a particularly solemn form of address, the conventional reversal of the normal word order to show deference to a superior party51. So that although no early formularies have been discovered – the first register which may have had that purpose was compiled by Master Hervé le Grant at the beginning of the fifteenth century52 – it is plain that there were established and regularly followed forms practised by Breton clerks throughout the period with which we are dealing. Ducal letters and grants were no longer written up, as they had once been in Brittany as elsewhere, by the beneficiaries, but in the chancery. Apart from the change from Latin to French as the normal language for the vast majority of documents written from c. 1280, the formulae used by John III (1312–41) or Francis II differed little from those used by Mauclerc. The introduction of new formulae – the phrase ‘par la grace de Dieu’ into the ducal title by 1417, for instance – thus had a deliberate political significance. It was a further step in the duke’s increasing assertion of his own independent sovereignty which marks the rule of all the late medieval dukes53.

[p. 694] The implication of these last few remarks is that there was tradition and continuity, the maintenance of archives and the training of clerks in the particular forms of letters issued in the duke’s name, even though little can be directly learnt of all this before 1341. As more records survive, so the range of business covered also expands until, inter alia, we find the duke exercising the whole range of powers which royal officials were anxious to reserve solely to the sovereign. He ennobled, enfranchised, legitimised, amortised, created notaries, fairs, markets and warrens, authorised fortifications, controlled taxation, struck money (including gold from the reign of Charles de Blois), enjoyed regalian rights during ecclesiastical vacancies, issued safe-conducts and pardons, even by the later middle ages, claimed the jurisdiction of cases of lèse-majesté54. And although the expansion of the political ambitions of the duke is sometimes signalled by the exercise of a right revealed by a new form of letter from time to time – John V, for example, particularly exercised his powers of ennoblement and promotion of those already within the ranks of the nobility – it would be wrong automatically to assume, in the absence both of diplomatic studies and of the fragmentary survival of the documents, that previous dukes had never exercised similar privileges55. But of the internal organisation of the chancery which produced this diverse range of records, at least before 1341, little is known.

We may presume that there was a succession of chancellors after Rainaud though the example of Burgundy where there was a break between c. 1210–70 may make us equally wary. The likelihood is that they were clerics but there is no definite evidence until mention of Macé le Bart, canon of Dol and Rennes, as chancellor in 1319. There is a tradition that he served John III for 15 years and that he had a hand in the compilation of La très ancienne coutume de Bretagne56. Later on there was Gautier de St-Pern, bishop of Vannes, who [p. 695] seems to have served under Charles de Blois for whom a number of other names have also been suggested as chancellors57. The habit of referring to the chancellor as ‘Vois’ in the list of witnesses from c. 1361 is a complicating factor since it deprives us on many occasions of certainty as to the identity of the chancellor concerned58. For this reason, when the duchy was still divided by civil war, we cannot be sure who it was who served John IV as chancellor – possibly John de Locminé, archdeacon of Vannes. But after 1364 other evidence is available and it is notable that at least three of John IV’s next six chancellors were laymen, signalling the end of a long clerical monopoly in the fourteenth century in Brittany as in other contemporary administrations. Though the post was to be held again by clerics in the first half of the fifteenth century, thereafter it reverted to laymen. Jean, vicomte de Rohan, in the fourteenth century and Louis de Rohan, sire de Guéméné and Philippe de Montauban, sire de Sens, in the fifteenth came from some of the most distinguished families in the duchy, though in the latter two cases they were from cadet branches, but the other lay chancellors emerged from more obscure backgrounds. Silvestre de la Feuillée and Jean de la Rivière were minor nobles and the latter was also a ‘maistre en medecin’59; others came from bourgeois families or from those of very recent noble status and owed their advance to their professional expertise in the law. They had often acquired their training by attending university and holding other administrative posts.

Once acquired the post might be filled for a long period: Jean de Malestroit was chancellor for thirty-five years from 1408–43, Guillaume Chauvin for 22 (1459–81) and Philippe de Montauban for almost thirty years (1487–1514), though he had a rival early in his appointment and was deprived of the title during Charles VIII’s reign. All three have attracted attention because of their important political role – John, duke of Alençon, considered Malestroit so influential with John V that he captured him in 1431, provoking a small war. The long-standing rivalry of Chauvin with Pierre Landoys, [p. 696] Francis II’s treasurer, has given rise to much discussion, particularly since their feud involved matters of principle over conflicting foreign policies. It ended in the cruel death of Chauvin, imprisoned at Landoys’ behest, and in the violent end of the treasurer himself in 1485, events which are part of the general history of the fifteenth-century duchy60. The story of Montauban’s career would also be worth telling in more detail. He first appeared in ducal service as a man-at-arms in the ordonnance companies in 1465 and he can be traced through other military and civil ranks until he became chancellor in September 1487. The next few years were especially hectic as he tried to protect Duchess Anne from the rival baronial cliques who wanted to use her as a pawn in a complex diplomatic game as the final war of independence was fought against France. He survived both personal misfortunes and considerable financial losses in the duchess’s cause, provoking after 1491 the hostility of royal councillors like Cardinal Guillaume Briçonnet by his uncompromising stand for Breton rights. But he emerged again as chancellor of the duchy in 1498, when he was able to rebuild his fortunes. His final solemn service to his mistress was his central role in the burial of her heart in the Carmelites’ church in Nantes in 1514 amidst much pomp. However, on his death shortly afterwards the position of chancellor of Brittany was amalgamated with that of the chancellor of France61. And what of other, lesser known, chancellors like François Chrestien, allegedly a pawn of Landoys, appointed to replace Chauvin, but who in 1485 refused to seal letters in which Landoys accused his enemies of lèse-majesté? He was, said the chronicler Alain Bouchart, who [p. 697] had probably served under him, ‘un homme simple et paisible’62. It would be interesting to know more about him and the other chancellors as influential political figures. Here, however, we must limit ourselves to a few further remarks on the role of the chancellor.

By the fifteenth century something of the dignity of his office can be gathered from his place on ceremonial occasions. In the funeral procession for Francis II, for instance, the seals of the duchy were borne before the chancellor on a square of velvet. Other members of the chancery, too, including no less than 24 secretaries received black cloth for mourning robes63. Montauban was similarly accompanied by the full chancery staff, maîtres des requêtes and secretaries in the vast procession to bury Anne’s heart. Elsewhere, in Parlement and at the États, chancery officials had their special positions. It was the chancellor who normally gave the speech from the throne on the latter occasions. It was he who summed up council discussions and gave the decisive opinion64. Among his most important public appearances in the later middle ages came to be the speech which he made on behalf of the duke at the ceremony where he rendered homage to the king of France. In the thirteenth century this homage was indisputably liege but from 1366 every effort was made by the duke to avoid pronouncing the, by now, distasteful words acknowledging his inferiority. When John IV first refused, royal officials were outraged as they continued to be as the same charade (as it has been called) continued to be re-enacted at every homage ceremony until Louis XI’s reign65. In the interim it was the chancellor who was called upon to justify his master’s refusal and his speech on these occasions needed to be a masterpiece of tact. Of course a compromise formula was reached – the duke performed homage ‘as his predecessors had done’ without specifically mentioning that it was liege homage. This usually satisfied both parties. But it was always a [p. 698] stern test and in preparation for it, as council minutes in 1461 make clear, careful arrangements had to be made beforehand to ensure that the duke’s case was not mishandled66. It was at these moments that the value of the chancery’s staff became apparent in providing the necessary briefs and actual documents to be displayed.

By this time, of course, the chancery was highly organised with a hierarchy of officials, including a vice-chancellor (first named in 1415), maîtres des requêtes and conseillers ordinaires (their role was described in the 1498 ordonnance succinctly for they were to serve ‘par quartier et signeront les lettres et mandemens en queue qui y seront deliberez et expediez’), a group of senior clerks, specifically called ducal secretaries, of whom one was sometimes singled out as the first secretary, a keeper of the seals and a keeper of the archives, other clerks and greffiers, normally between 20–30 officers in all67. But two hundred years earlier things were very much less formal. It may be presumed that c. 1300 the chancellor normally held the great seal (as he did later in the century), that his remuneration was chiefly from fees charged for the issue of letters, that the records of chancery were deposited in various ducal residences or religious houses and that for normal business there were a few scribes in attendance on the duke. Accounts occasionally reveal the names or numbers of the resident clerks in the household – seven are listed in a document of 1305 – and it may be suspected that these were the principal chancery officials at that moment68.

[p. 699] Numbers grew only slowly; in the late fourteenth century there were probably six or eight clerks simultaneously writing ducal letters, of whom three or four might specifically be called secretaries69. Amongst these latter there were also by this stage some important members of the duke’s entourage, councillors who went on diplomatic missions and held other posts in the administration, which clearly left them little time to work daily in the chancery. As a result the numbers of secretaries and clerks tended to inflate, a tendency which continued modestly through the fifteenth century. In the household regulations of 1404 two secretaries had ‘bouche à cour’ and 50 l. p.a., Guillaume Bruneau, ‘secretaire et controlle’ had ‘bouche à cour’ for himself and his clerk and 80 l. p.a. whilst two other secretaries ‘de la chancellerie’ received 40 l. p.a.70. A few years later Blanchard found that ten or twelve clerks were already at work concurrently in the chancery and the same picture emerges from the first surviving registers when between 12 and 15 clerks, on average, seem to have been authorised to issue and enroll letters at any one period71. Nevertheless a few stand out for the regularity and volume of letters they wrote72. As with other household positions, chancery clerks sometimes [p. 700] worked a rota system, whereby some remained in the chancery for a set period – three months seems to be an average stint – before being relieved73. This need for duplication would account for the 24 named chancery clerks in the beguin of Francis II in 148874. On the other hand, the first secretary and some other leading officials, the keeper of the seals, for example, appear to have remained on duty almost constantly. Among the reforms proposed by Charles VIII in 1493 was the reduction in the number of secretaries to eight. In 1498 Anne authorised ten and in the early sixteenth century the numbers of chancery employees remained fairly constant, though two men or more could on occasion share one salary75.

By this period the council and chancery were normally expected to perform their duties chiefly in Nantes and Rennes (Anne’s ordonnance stipulated alternating periods of a year at each location) though both could still be peripatetic as is evidenced by their activities when accompanying Anne in her pilgrimage and triumphal tour of the duchy in 150576. At earlier dates most chancery work was performed in the normal administrative centres of the duchy – Nantes, Rennes and Vannes – often in houses owned or hired by the chancellor for the purpose, though by the late fifteenth century the majority of records seem to have been moved principally to the castle at Nantes77. The house in which Jean de Malestroit lived as chancellor in Vannes – Château [p. 701] Gaillard – still stands, whilst Guillaume Chauvin occasionally delivered letters at his manor house just outside Nantes and Philippe de Montauban frequently despatched business at his manor of Bois de la Roche78. Sometimes the absence of the ducal household or of the chancellor was useful as an excuse to delay the issue of letters79. On the other hand both the chancellor and vice-chancellor might take advantage of visits to different parts of the duchy to issue letters on the spot80. Naturally the duke acted in the same fashion wherever he was within or outside the duchy.

In the absence of registers before 1462 there has been some speculation on the volume of ducal letters issued in relation to the proportion now surviving. Blanchard thought that on average six or seven letters a day were issued from John V’s chancery, which led him to calculate that some 90,000 might thus have been written in the course of that reign81. However this figure probably ought to be revised downwards, perhaps by as much as a half, for the annual enrollment in Francis II’s early registers totals about 1000 letters while the fragment of the daily register of letters for which fees were charged for the period 24 October 1489 – February 1490, shows that not such a large percentage of letters as was once thought escaped registration. The registers also show that normally sessions were not held daily for the issue of letters but every two or three days or even after longer intervals – in 1506, for example, there were less than 100 sessions at which letters were authorised. This leads me to suggest that an average of 4 or 5 a day seem to have been issued in the late fifteenth century, hardly an intolerable workload for the dozen or [p. 702] so leading clerks and an added reason, perhaps, for Charles VIII’s desire to reduce their numbers82.

Whether the Breton chancery clerks developed any form of collegiality or received any corporate privileges like the royal notaries and secretaries, we cannot say at the moment. As individual figures chancery clerks only begin to emerge from their anonymity during Charles de Blois’s reign. In addition to signing letters, a number of them gave evidence at the hearings intended to establish his sanctity, held at Angers in 137183. From this testimony, in addition to personal information of considerable interest, it is clear that many features of the chancery’s activities which can only be easily documented from a later period, were already well established. For example, in normal circumstances and in conformity with other contemporary chanceries, fees were exacted for letters of grace and justice and it was from these that the chancellor was rewarded84. Later there is evidence that he was often also in receipt of a pension, which either supplemented or recompensed him for these fees, and of an allowance for daily attendance in the chancery and council85. Henri le Barbu, chancellor from 1386–96, received 1000 l. a year as a pension, but it could be a smaller sum86. A hundred years later, Philippe de Montauban received a pension and fees which sometimes amounted to as much as 4000 l. [p. 703] p.a.87. By then the normal pension of the vice-chancellor was 600 l. p.a., maîtres des requêtes received 300 l. p.a., whilst secretaries could usually expect annual salaries (in addition to robes) in the range 40–200 l. depending on seniority, figures which seem to have remained fairly stable throughout the century, though Master Henri Milet as first secretary to Francis II received the exceptional sum of 240 l. p.a. Conversely, after 1498 the normal pay of a secretary fell to 100 l. p.a.88. Of course there were other rewards as well, since the clerks were in a position to promote their own interests, but the payment of salaries was not always guaranteed. Towards the end of Francis II’s reign a proportion only of the salary – ten months, six months or even no wage at all on occasion – might be paid as desperate attempts were made to meet all the duke’s commitments89. Like civil servants in other administrations who faced similar demands, they were sometimes called upon even to make loans to the duke90. However, when the annual income of many Breton gentlemen [p. 704] and lesser nobles was often less than 100 l. a year, the regular financial and other rewards of service in the chancery must nevertheless have appeared attractive enough during the latter half of our period. For the higher officials, there were other opportunities, too, to accumulate modest fortunes. The total wage bill for the chancery between 1498–1512 came to 91,270-11-7 d, approximately 6300 l. p.a.91.

To return to the chancery in the mid-fourteenth century: according to some witnesses in 1371, the volume of business was already considerable. Guillaume André alone claimed, in exaggerated fashion, that he had written over 10,000 letters during his time as secretary92. He and others testified with surprising approbation that a number of office rules had been broken by order of the duke when it was a matter of rendering justice to his poverty stricken subjects. We thus hear of Charles de Blois waiving fees, issuing letters freely to paupers (some of whom received their letters on the spot after accosting the duke in the countryside, his clerks having to dismount there and then to write the orders), getting his secretaries to write letters outside normal hours by night and even dipping into his own pocket to provide parchment and, significantly, paper for his clerks93. All of which speaks highly of the flexibility of this group of civil servants in accepting the foibles of their eccentric and saintly master. It was a similar flexibility that some of them showed when they transferred their allegiance after his death in the battle of Auray, 29 September 1364, to his rival and successor, John IV. Among those who made this transition was Master Guillaume Paris, reputedly once chancellor [p. 705] for Blois, later certainly dean of Nantes and one of the leading councillors of the new duke94.

What of the quality and experience of these fourteenth century clerks? Most of those named in 1371 were, of course, in religious orders. Virtually all those who styled themselves secretary had been to university, though there were some who seemed either to have been trained within the ducal administration or to have had notarial training. A good example is Rolland Poencé, from Goudelin in the diocese of Tréguier, aged 53 when he gave his testimony. He had known Blois since his marriage to Jeanne de Penthièvre in 1337. He had served successively as a clerk and notary ‘in curia senescallorum’ for fifteen years, then as alloué (a chiefly legal post) and lieutenant to the seneschal of Guingamp, followed by another spell of fifteen years up to Charles’s death as one of his secretaries, a position which he held simultaneously for the last four years with that of seneschal of Cornouaille95. Similar career patterns can be established from this point for many of Poencé’s colleagues. Of the 15 clerks whose signatures appear at the foot of Blois’s letters in Maître’s catalogue, four testified in 1371 as did the brother of a fifth, while the names of three additional ducal clerks and secretaries can be added if the details of the testimonies can be trusted96. They and others like them, who began their careers in other ducal courts – the later registers reveal the names of scores of such clerks and notaries who never rose above these minor jurisdictions – might expect employment once within the chancery for thirty years and more97. Guillaume André, originally from Le Mans, had known Blois for 31 years and spent the last 24 with him as a notary98. Geoffroy le Fèvre, who first comes to attention in the court at Morlaix in 1346, was still in ducal service in the mid 1380 s99. The same pattern continues through the fifteenth century. The social origins of these clerks was mixed, with a preponderance, not surprisingly, of bourgeois and lesser nobles, and the network of brothers, [p. 706] fathers and sons, uncles and nephews soon becomes all too apparent. Frequently success led to ennoblement in the fifteenth century of those lacking noble lineage.

Charles de Blois rewarded some of his servants in the traditional fashion by helping them to obtain ecclesiastical benefices or by providing them with pensions. Alain Raoul had been a scholar at Paris before becoming a secretary for three years before Blois’s death; in 1371 he was rector of Plouzévedé in the diocese of Léon100. Master Rolland de Coestelles, a graduate in arts and law, who had spent twenty years with Blois and his children ‘tam serviendo in capella … et instruendo dictos liberos in scienciis litterarum quam in officio secretarii’, including several years with Blois during his English capitivity, was now a canon of the cathedrals of Nantes, St-Pol de Léon and Angers101. Yet others might move on to different administrations like Mr Jean Vitreari who claimed in 1371 to be a royal secretary after spending five years with Blois102. Whilst yet others were considered influential enough with their master to warrant a pension from a foreign prince like two secretaries of John IV, Richard Clerk, who received one from Louis, duke of Anjou103, and Master Robert Brochereul, one of the chief negotiators of the duke’s third marriage to Juana of Navarre. Her father, Charles II, gratefully acknowledged his services by granting him 500 Aragonese florins a year104. As in other administrations a bishopric was the ultimate reward for a few of the outstanding secretaries. Among the clerks of John IV were Gacien de Monceaux, later bishop of Quimper (1408–16) and Master Alain de la Rue, later bishop of St-Brieuc (1419–24), where he succeeded Chancellor Malestroit105. Later Guy du Boschet and Guillaume Gueguen had served Francis II as secretaries before becoming vice-chancellors. Boschet was elected bishop of Quimper (1480–4) and [p. 707] Gueguen after a prolonged battle, bishop of Nantes (1500–06)106. But lesser dignities were not spurned; Macé Louët, one of the leading chancery officials at the turn of the fifteenth century became archdeacon of Vannes and then also of Dreux107.

Increasingly, however, many clerks were not simply satisfied by the rewards of celibacy but married and established families. An early example is that of Pierre Poulard, one of Blois’s leading advisers108. Like those royal notaries and secretaries in the later middle ages whose careers, social advance and family connections have in recent years been so remarkably traced by MM. Lapeyre and Scheurer, or the councillors of the fifteenth-century dukes of Burgundy studied by M. John Bartier, within the more limited context of Brittany’s history similar success stories can be described109. One example, which will have to serve for many, is that of Master Robert Brochereul just cited.

Little is known of his family background before he emerged as a member of the ducal administration in the early 1380 s. Possibly of bourgeois stock from Nantes, certainly a minor landholder in the Pays de Rays and a graduate in law from the university of Angers, he held a succession of important offices such as seneschal of Nantes and Rennes before becoming chancellor from 1396–9. Though his name does not appear amongst those of the clerks signing ducal letters, he is styled ducal secretary in documents connected with his mission to Navarre in 1386 and he undertook many other confidential missions, to the English and French courts in particular110. As his status rose, [p. 708] so did his material fortunes and although he left only daughters, his eldest married into the prestigious Montauban family and was grandmother of the last chancellor of the duchy111. Though replaced as chancellor on John IV’s death in 1399, Brochereul continued to sit in John V’s council till 1410 at least112.

Throughout the fifteenth century the network of family alliances between the duke’s servants in all the offices of his administration – council, chancery, chambre des comptes and the local legal and financial offices – became ever denser113. Master Hervé le Grant, the prime organiser of the late fourteenth-century ducal records, married into the Mauléon family who were to prove one of the major bureaucratic families of the fifteenth century114. The names of Breil, Carné, Chapelle, Chauvin, Coëtlogon, Coglais, Ferron, Gibon, Lespervier and Mauhugéon, to name but a few families in this tangled network, constantly reappear amongst the chancery clerks and other office holders from this point115. Nor were relations limited simply to the duchy, but stretched to the royal and other princely administrations like the case of Master Henri Milet, for long first secretary to Francis II. His father, Jean, a royal clerk, had been ennobled by Charles VI before 1419 and lived until 1463. His other sons included Jean, bishop of Soissons, Eustache, a councillor in the Parlement of Paris, and Pierre, who served the duke of Burgundy116. Henri first comes to attention in the service of the Constable, Arthur de Richemont (the future Arthur III) in 1439 and from then until his death in 1477 he was at the centre of Breton politics117. Latterly he was particularly responsible for coordinating the diplomatic correspondence of Francis II and his allies against Louis XI. [p. 709] I treasure a reference to the king and his agents in 1471 in true cloak and dagger fashion piecing together the charred remains of some incriminating coded letters discovered after one of Milet’s secret journeys to Guyenne to Charles, Louis’s brother, as evidence for this world of intrigue into which the formal records of the chancery so infrequently allow us to penetrate118. That Henri took his chancery duties seriously may be gathered from the fact that he acquired the legal books and working papers of Master Jean Lespervier in 1473, when this member of another established bureaucratic family, defected to Louis XI119. A prosopographic study of the fifteenth-century chancery clerks would reveal many similarly intriguing connections and enable us to plot more exactly their place in the social structure of the duchy, their intellectual interests and attainments, the range of their religious and artistic patronage120. But we must return to the central political role of the chancery in Brittany during the later middle ages.

It had long been realised that defence of ducal rights, both against his own subjects, but more importantly against the claims of the king of France, his sovereign, might be more effectively countered by the production of documents supporting the ducal point of view. Even before the civil war began in 1341, there is evidence that claims based on both actual records and legendary materials were coming to play a part in the thinking of the duke and his council in the preparation of legal defences121. Once formulated the arguments [p. 710] could be valuable to future ducal governments and the details revised or reinforced by further evidence. It was chiefly the responsibility of the chancellor and his staff to produce such evidence from their records. Given the initially unpopular victory of the Montfortists (aided by the English) in the civil war and the shaky position of the ducal administration for much of John IV’s reign, it is not surprising that he and his advisers should seek to make full use of this relatively cheap form of propaganda. They attempted to build up quite deliberately an image of an independent identity for the duchy of Brittany which would appeal to local pride, stimulate loyalty to the Montfort dynasty and limit the authority of the king of France within the duchy122. Its worth has already been glimpsed in connection with the question of the duke’s homage; by the 1380 s it was being put to similar use to justify other pretensions. In particular a group of chancery clerks, headed by two ducal secretaries, Master Guillaume de Saint-André and Master Hervé le Grant, seem to have coordinated literary and administrative moves to create a Montfortist mythology which was to serve the rulers of the duchy until its incorporation in the kingdom of France. Saint-André’s major literary contribution was a eulogistic biography in verse of John IV to demonstrate triumph over adversity and his writings show that he had an abiding interest in the mutations of fortune123. As for Hervé le Grant, his well-established role as the organizer of the ducal archives has already been touched upon. Besides his inventory of 1395, he compiled a formulary (c. 1407–8), a similar collection of papal bulls and either undertook himself, or had copied under his supervision, other copies of important documents. Some of these were of considerable antiquity like the ordonnance of John I in 1240 expelling the Jews from Brittany which Le Grant attested in a public instrument in 1397 or the fine copy of the Livre des Ostz of 1294, together with documents relating to the duke’s homage, which he had copied at much the same time as his formulary124. He was to hold the position of ‘tresorier et garde des lettres et chartes’ [p. 711] until 1416 and one frequently comes across documents endorsed with notes like ‘Doyt estre et a portee a mestre Herve’ and other indications of documents confided to his keeping125.

As a result it is not surprising, perhaps, that in recent years opinion has been swinging strongly to the view that Hervé le Grant is the most likely author of an ambitious although incomplete history of the duchy, for long inaptly entitled the Chronicon Briocense126. Its tone can be gauged from a recent comment that it was written by ‘un fougeux patriote breton, chez qui l’amour du pays s’accompagnait d’un violent sentiment xenophobe à l’égard des Anglais et des Français.’ Whoever the author was, he was an expert on Breton and was an ardent defender of the church. ‘Il regrettait la scission au moment du Grand Schisme d’Occident. Ses sympathies allaient aux clémentistes, mais plus encore à l’Église universelle127.’ He was also someone who had easy access to the ducal archives – no fewer than 34 ducal letters and 5 papal bulls are cited verbatim in the chronicle – and also had inside knowledge of the workings of the ducal council and a familiarity with notarial practices. No one better fills this description than Le Grant, a native of the diocese of Quimper and a graduate of Angers, who entered ducal service in 1379 at the beginning of the great schism128. He was a qualified notary, and a man who throughout his professional career came to have an intimate knowledge of [p. 712] the ducal archives and of the family affairs of John IV129. A frequent member of diplomatic missions, closely associated with all aspects of ducal policy, no one would have known better where to find the documents which have been summarized, quoted verbatim or invented in the Chronicon Briocense, which provides a classic statement of the Montfortist view of Breton History130. Hervé would have been by no means a unique example of a princely archivist in the fifteenth century who put his expert knowledge to good use in writing history – the house of Foix employed several such figures as the value of records for propaganda purposes became more widely appreciated131. Whilst in Brittany itself another burst of similar and more distinguished literary activity in the late fifteenth century was again spearheaded by two ducal secretaries, Pierre le Baud and Alain Bouchart, both of whom were fully aware of the political value of their histories to the defence of Breton interests132.

The Breton court, more particularly the chancery, as a centre of historical studies in the later middle ages seems a well established fact now. But chancery clerks did not spend all their time composing or inventing history. It is tempting to link Hervé le Grant’s name with an important step in enabling the administration to keep track of its records for more prosaic purposes, that is the introduction of registration. Given his orderly mind and notarial training (unfortunately no Breton notarial registers survive until the late fifteenth century)133 and the fact that it was during his period as keeper of the archives that registration seems to have first been extensively practised, it may seem logical to see Hervé’s hand in this innovation. However, another candidate as originator of the idea may have been Hervé’s one-time senior, Henri le Barbu, chancellor of the duchy from 1386–96. For it was shortly after Le Barbu transferred from Vannes to the see of Nantes in 1404 that he ordered the [p. 713] compilation of baptismal registers throughout his diocese134. But whoever promoted the idea, both the fragmentary chancery registers of John V and the parochial registers of Nantes (curiously the first full surviving registers from both series now begin in 1462 and 1464 respectively) testify to the systematizing surge that was sweeping over the duchy c. 1400. Their value was increasingly appreciated whilst at fairly regular intervals throughout the rest of the century, inventories of the archives were prepared which enabled appropriate records to be produced for envoys going to defend the duke in Paris or elsewhere135. From the mid-century in particular diplomatic bags containing lists, originals or copies, dossiers which could be revised almost immediately, stood ready for use and were quickly brought out in emergencies. A case in point was the quarrel over the régale at Nantes in 1462 which M. Contamine has recently investigated136. There he found that the royal administration on this occasion, unlike its ducal counterpart, had virtually to start from scratch to find the documentary justification for its position, whereas the duke began with a long tradition of defending his claims which had resulted in the creation of a whole archive of records to be brought into the argument137. When royal commissioners were sent to gather information in the duchy, they were accompanied round it by ducal servants anxious to gather yet further material for their own dossier138. Another contentious issue which had resulted in a similar file was the disputed jurisdiction of the Breton marches discussed over [p. 714] the years by a succession of commissions139. Yet another, of course, was the question of homage. On the eve of his journey to Tours in 1461, the council not only discussed ‘que sont a besoigner touchant le voiage’ but prepared statements on what Francis II was to say to Louis XI and what documentary evidence he wae to display, ‘et a servir a cest article le tresor des lettres baillera au vichancelier les lettres et instruments des precedentes hommages tant de la part du duc que de la part du roy140.’ Over the years, under the obvious guidance of ducal councillors, as in two great inquiries in 1392 and 1455, other testimonies had been gathered around the duchy on what the duke was pleased to call his own ‘regalities’ with a view to providing a suitable defence of his exercise of these rights141. Within the chancery whenever the word was mentioned there was an almost pavlovian reaction and a standard recitation of what this meant in practice was produced automatically. Themes first elaborated in John III’s reign were thus constantly repeated, refined or expanded by chancery officials in defence of the duchy142.

By the fifteenth century, then, the Breton chancery was highly organised with professional personnel, clearly established office procedures, carefully following its own rules for the formulation of letters, the application of seals and registration, and it played a crucial role in the defence of the duchy’s political stance. Though it had not developed many distinctively different procedures from those practised in other French chanceries, its letters had their own characteristics, idiosyncrasies of language and style and decoration143. [p. 715] Apart from recourse to public instruments – a particular characteristic of John IV’s reign, but one also practised by other dukes for a wide range of business – the competence of the chancery to handle all forms of document was unquestionable144. From time to time efforts were made to tidy up aspects of its administration – the ordonnances in 1404, 1493 and 1498 are reasonably well documented – some attempted reforms in the mid-1450 s less so. In a brief and still too little understood reign, Peter II undertook an almost complete overhaul of the duchy’s administration145. In the case of the chancery he confirmed the traditional fees for the issue of letters. These were halved briefly by his successor, Arthur III, but returned to their usual level in Francis II’s reign146. As a further sign of the tightening up of the administration from the mid-century, in the chancery as in some other departments, continuous appointments can be traced to offices which had lapsed or been left vacant in the recent past. Thus regular appointments of vice-chancellors, keepers of the seals and other subsidiary posts within the chancery begin again147. Posts were now normally filled only on the death or resignation of the previous occupant. By the late fifteenth century great care was often taken to ensure the safety of the seals, with elaborate rituals developing for their handover or guardianship148. The registers contain many notes on the particular circumstances of the issue or cancellation of letters, use of seals of absence and fees to [p. 716] be exacted149. The signatures of others members of the administration who had come to chancery to collect particular records, to note their delivery or return, and so on, also occasionally appear. At the end of each session’s business the presiding officer – the chancellor or his deputy – now added his own signature to conclude the day’s work and to ensure against unauthorised enrollment150. The neat business-like registration of letters and his concern for minutiae encourages a generally favourable impression of the efficiency onf the chancery at this stage.

But it would be remembered that appearances can be deceptive sometimes. The witnesses in the 1371 inquiry at Angers were unanimous in praising the concern of Charles de Blois to appoint just officers in all levels of his administration151. But there were occasional lapses in probity. It has already been seen that the duke might inadvertently grant letters with contradicted earlier ones, appointing two men to the same office, for instance, and one can occasionally suspect an element of bribery, other pressures or simple ignorance152. More seriously, an inquiry into the misconduct of Chauvin and his staff in 1463, shows how relatively easy it was for chancery clerks to engage in fraudulent practices. In this instance they had apparently conspired to issue blank safeconducts which were then sold to English and German merchants wishing to trade in the duchy in contravention of a general prohibition by Louis XI. It is impossible here to unravel all the intricacies of the plot which involved some of the most senior members of the chancery, possibly the chancellor himself153. Public confidence had been shaken and morality outed, it was alleged, by these events. Olivier du Breil, the proctor-general, called [p. 717] for a searching investigation, a powerful commission was appointed and eventually many serious charges about the breach of chancery practices were layed against the chancellor154. It was even claimed that through his actions the very safety of the prince and duchy had been imperilled, that he had indeed committed crimes which amounted to lèse-majesté155. But for reasons about which we cannot be clear, Francis II chose to forgive most of those involved with the plot. Giles de Cresolles, the chancery clerk most deeply involved (homme feable, said Jacques Raboceau, his senior) is no longer found signing the register but no one else was dismissed, despite incriminating confessions; blank letters and letters with windows as they were picturesquely called, were later still used for some kinds of business156. But it was an episode which rankled and Chauvin’s reputation as chancellor never entirely recovered, for although he survived this first serious assault on his position, the charges were to be resurrected many years later in 1482 by his bitter rival, Landoys, to justify his ultimate dismissal157.

[p. 718] As for the technical competence of the fifteenth-century chancery there is another minor incident which may be used to show it up in rather poor light. It was normal for original letters to be produced before the council when privileges needed to be checked. In the surviving minutes for 1459–63 this procedure can be observed on several occasions as in November 1459, when the rights of the abbey of St-Melaine to enjoy certain privileges in the forest of Rennes were inspected. A number of original ducal letters were exhibited including those of Conan III (1128), Duchess Constance (1193), John III (1333) and one of 1379 ‘contenant une sentence’158. A year later the countess of Laval displayed letters of John IV (1395) to support claims in a dispute with the duke over her possession of the barony of Vitré and she followed this up with even older letters of 1235, whilst the ducal proctor countered with a whole series of aveux ‘estans ou tresor dou duc’159. But the ability of the councillors to apply their critical faculties to the examination of some of these letters must be called into question when, in December 1462, the lord of Derval produced before them one of the most handsome forgeries in a duchy renowned for such productions in the later middle ages160. These were allegedly letters of Arthur II ‘soeant en nostre general parlement o la solemnipte de nos troes estas’ by which he granted to his kinsman Bonabé, lord of Derval (by a mythical descent from ‘nostre feu oncle Salmon jadis conte de Nantes’) the right to include two plain quarters of ermine in his family arms161. According to the secretary, who wrote the council minutes – probably Pierre Raboceau, one of those implicated in the scandal of 1463 – these letters supposedly granted on Monday after St Mark’s day, 1306, were ‘saines et entieres en escripture, signe et seel’. They bore a seal on silk laces displaying the arms of Dreux with an ermine quarter (Brittany) and the legend ‘S. Parlamenti Britanie’162. Although the attention of any alert chancery clerk should have been immediately aroused by letters which began ‘A tous les oeans et voeans ces presentes, Artur par la grace de Dieu duc et prince de Bretaigne …’ no comment is made on their authenticity. It is unfortunate that the laconic minutes do not provide further detail on the context for the production of these letters in council. The evidence is that they had been forged in [p. 719] the very recent e, possibly at much the same time that Peter II promoted Jean, lord of Derval, to the rank of one of the nine ancient barons of Brittany in 1451, in order to explain the appearance of the ermines of Brittany in the Derval arms163. Perhaps the fact that this original forgery still survives in the former ducal archives should be taken as indicating that someone in the council meeting in December 1462 was not quite so credulous as his colleagues164. And to be fair, it must be pointed out that other forgeries were detected and measures were frequently taken to try to end fraudulent practices in the fifteenth-century duchy165. The duke enjoyed the confiscated property of convicted forgerers. Prosecutions did occur, though he also exercised clemency towards offenders166. There continued to be a certain ambivalence in the attitude of officials; after all there were occasions when the ability to fabricate documents might be useful to the state as the work of the chancery historians shows! It is thus doubtful whether in the end he Breton administration was in this respect any different, more corrupt and inefficient, than other contemporary administrations.

It is perhaps right that this survey of the history of the Breton chancery should conclude with some remarks on the strengths, weaknesses and failings of its personnel. The registers show how well placed its members were to forward their own private interests, sometimes at the expense of the state. More often their rewards were considered legitimate perquisites – the registration of letters on their behalf, taking advantage of the fact that they were often the first to learn that an office was vacant, a plot of land available, the farm of [p. 720] a lucrative source of revenue about to be renewed. The first grant in the first surviving register is to the chancellor, Guillaume Chauvin or, more probably, a namesake167. He was in a position also to speed the prosecution of those who infringed his rights like those caught fishing his lakes in 1464, to register a grant of a fair at St-Leger in 1473 or the enfranchisement of properties or to forward his claims to other inheritances168. And what the chancellor could arrange, mutatis mutandis, so could his subordinates169. Whilst those outside the chancery knew that its employees were influential and their cooperation essential if certain titles were to be established. Only more prolonged study of its personnel will reveal the parameters of acceptable behaviour, the baffling and dense family connections and the extent to which the chancery was the lynchpin of the duchy’s administration, the source of its political propaganda in the struggle with the crown, the ultimate guardian of Breton liberties.

After more than two centuries of continuous existence described briefly here, the first half of the sixteenth century saw the disappearance of the chancery as it had been developed in the service of the dukes of Brittany. The first ominous indications of what was to be royal policy had manifested itself in the suppression of the chancellor’s title between 1493–8. There followed a brief Indian summer after 1498 and while Anne lived her council and chancery in Brittany still had an important role in the affairs of the duchy. But with her death on 9 January 1514 and that shortly afterwards of her devoted chancellor, Philip de Montauban, the tightening grip of the royal administration became apparent. There was room in France now for only one chancellor; the office in Brittany was merged with that of chancellor of France. A non-Breton from one of the most powerful royal bureaucratic dynasties, Jean Briçonnet, was appointed vice-chancellor and it was he who now directed the Breton council and chancery170. As late as 1539 Francis I once more confirmed the chancery’s existence but the fundamental political role which council and chancery had played under the Montfort dukes had long since ceased. Finally in November 1552 its judicial duties were taken over by the présidiaux courts [p. 721] and the Parlement de Bretagne assumed responsibility for the registration of public acts171. But as far as the late medieval phase of the chancery’s history is concerned this ended symbolically on 19 March 1514 when in the church of the Carmelites at Nantes ‘led. chancellier print le cueur de ladicte dame (Anne) et au devant de luy le roy darmes Bretaigne … descendirent soubz celle voulte … et la fut pose le cueur de la magnanime dame en ung coffre dacier fermant a clef entre son pere et mere …’172.

[p. 722] Appendix I: A provisional list of chancellors of Brittany, 1213–1514

| Name | Acting | Other posts | References |

| Rainaud d. 1245 | By March 1214–1236 at least | Bishop of Quimper 1219–45 | Levron, no. 9 (1214); Bib. nat. MS. 9035 fo. 6 no. 2 (1219); Bull. diocésain… Quimper, 1911, 249 no. 35 (1236). |

| Macé le Bart | 28 March 1319 | Canon of Dol, Rennes and St Martin de Tours, scholastic of Nantes (1321–3), chanter of Dol (1323–40) | G. Mollat, Études et documents sur l’histoire de Bretagne, Rennes 1907, pp. 54–5. |

| Gautier de St-Pern173 d. 1359 | Between 30 April 1345 – 14 May 1346 at least | Bishop of Vannes 1346–59 | Arch. dép. Pyrénées-Atlantiques E 624 no. 1 fos. 5–8 |

| Jean de Locminé d. 1365 | Between 8 Feb. 1361 – 4 May 1365 | Archdeacon of Vannes | Recueil Jean IV, i. nos. 8, 33, 43–5. |

| Hugues de Montrelais d. 28 Feb. 1384 | By 27 Jan. 1366 – 28 Nov. 1372 at least | Bishop of Tréguier 1354–7; bishop of St-Brieuc 1357–84; Cardinal 1372 | Recueil Jean IV, i. no. 66; Lettres secrètes de Grégoire XI, no. 1010. |

| Jean, vicomte de Rohan d. May 1396 | By 26 Sept. 1379 – 5 May 1384 | Recueil Jean IV, i. no. 320; ii. 493 | |

| Silvestre de la Feuillée d. after Oct. 1392 | 8 June 1384 – 6 June 1385 at least | Recueil Jean IV, ii. nos. 511, 521, 546. | |

| [p. 723] Henri le Barbu d. 27 April 1419 | Probably by 19 May 1386 – 18 July 1395 at least | Abbot of Prières (1381); bishop of Vannes 1383–1404; bishop of Nantes 1404–19 | Recueil Jean IV, ii. 582; Bib. Nat. MS. français 22319 p. 154. |

| Robert Brochereul d. after May 1414 | 1 August 1396 – Nov. 1399 at least | Seneschal of Nantes and Rennes | Recueil Jean IV, ii. no. 1063; Preuves, ii. 697, 699. |

| Mr Etienne Ceuret d. 6 Dec. 1429 | July 1401 – before 7 Jan. 1404 | Bishop of Dol 1405–29 | Lettres de Jean V, no. 734. |

| Anselme de Chantmerle d. 1 Sept. 1427 | 7 Jan. 1404 – at least 18 May 1404 | Bishop of Rennes 1390–1427 | ibid., no. 2; Preuves, ii. 740. |

| Hugues Lestoquier d. 10 Oct. 1408 | By 18 Nov. 1404 – April 1408 | Bishop of Tréguier 1403–4; bishop of Vannes 1404–8 | Lettres de Jean V, nos. 20, 1025 |

| Jean de Malestroit d. 14 Sept. 1443 | Between 9 April / 20 June 1408–1443 | Bishop of St-Brieuc 1405–19; bishop of Nantes 1419–43 | ibid., nos. 1027, 1029, 1034, 1251 |

| Louis de Rohan, sire de Guéméné d. 1457 | 1445–50 | Preuves, ii. 1395; Mathieu d’Escouchy, Chronique, iii. 247; E. Cosneau, Le connétable de Richemont, Paris 1886, p. 388. | |

| Jean de la Rivière, chevalier d. after 1461 | By 3 Nov. 1450 – before 27 Sept. 1457 | Preuves, ii. 1545, 1554, 1605–6, 1671, 1686, 1708, 1725; iii. 38. | |

| Mr Jean du Cellier d. by 9 Aug. 1468 | 27 Sept. 1457–1458 | Seneschal of Rennes; alloué of Vannes | ibid., ii. 1710, 1733. |

| [p. 724] Guillaume Chauvin d. 1484 | By 28 Feb. 1459–5 Oct. 1481 | Trésorier de l’épargne; trésorier général; président de Bretagne | Bib. Nat. MS. français 11549 fo. 134; Preuves, ii. 1741. |

| Mr François Chrestien | June 1484–1485 | ALA, E 212 no. 17 fo. 6r; Preuves, iii. 446, 461–3. | |

| Mr Jacques de la Villeon d. by 19 Sept. 1487 | Sept. 1485–1487 | Procureur de Lamballe; seneschal of Rennes | Preuves, iii. 484, 577; ALA, E 2–9 no. 23 fo. 12. |

| Philippe de Montauban174 d. 1516 | 20/23 Sept 1487–1514 | Seigneur de Sens et du Bois de la Roche; captain of Montauban and Rennes | Preuves, iii. 541, 694, 757, 923–4. |

[p. 725] Appendix II

A. Types of letters issued according to the register of fees from 24 Oct. – 1 Dec. 1489 (ALA, E 212 no. 21).

| October | November | December | Total | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 24 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 1 | ||

| Mandement | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 14 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 74 | ||||

| Institution | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 14 | |||||||||||||||

| Rémission | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sauvegarde | 4 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 34 | ||||||||||

| Commission | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Saufconduit | 1 | 9 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 20 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Congé | 1 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 25 | |||||||||||||||

| Décharge | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Confiscation | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Respit | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Excuse | 2 | 2 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Donation | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 6 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Déport | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rabat | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Evocation | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Relèvement | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sourcéance | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maintenue | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ordonnance | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sûreté | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Restitution | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prorogation | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Change | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | 13 | 19 | 13 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 3 | 11 | 2 | 6 | 9 | 38 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 9 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 207 | |

[p. 726] B. Types of letters issued according to the chancery register from 24 Oct. – 1 Dec. 1489 (ALA, B 12).

| October | November | December | Total | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 24 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 2175 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 12 | 14 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 20 | 22 | 23 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 1 | ||

| Mandement | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 4 | 9 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 66 | ||||

| Institution | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 12 | |||||||||||||||

| Donation | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Rémission | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sauvegarde | 5 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 35 | ||||||||||

| Commission | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Saufconduit | 1 | 10 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 23 | ||||||||||||||||

| Evocation | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Congé | 4 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 20 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Décharge | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Respit | 2 | 1 | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Excuse | 2 | 1 | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dépot | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rabat | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Relèvement | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sourcéance | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maintenue | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ordonnance | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sûreté | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prohibition | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prorogation | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Restitution | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | 13 | 18 | 13 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 3 | 10 | 2 | 5 | 8 | 32 | 8 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 9 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 196 | |

[p. 727] Appendix III.

Francis II orders the chancellor and the other officers who preside in his council to accept letters sent to them by Guyon Richart and Guillaume Gueguen, secretaries, to which the duke’s signature has been added by means of an engraved stamp, Nantes, 6 May 1483 (ALA, E 128 no. 6 (anc. N.H. 31), original parchment, 350 × 219 mm, formerly sealed on a tongue, with a tying thong).